Work in Progress is an interview series with independent curator, writer and cultural worker Alyssa Alexander, that spotlights an emerging or mid career artist, allowing them to explore facets of their individual practices, share works in progress, and connect with overarching contemporary themes. Each iteration will have artists answer questions tailored to their work, but culminate with the same five questions.

Carlos Rosales-Silva is a painter and muralist living and working in New York City. His art and research practices center the histories of Brown people in the United States, and the layered visual culture within their communities. Foundational to his work is also a meditative approach to the “landscape”- his upbringing in the American southwest shaping his gaze. Rosales-Silva’s latest show, Sunland Park, brings together three distinct bodies of work that challenge the notion of painting and explore infinite possibilities of color and texture. In this conversation we discuss information-sharing as an art form, the complex playfulness of abstract painting, and how the desert will undoubtedly change my life.

Alyssa Alexander: What makes you still call these paintings, even though they're very much...

Carlos Rosales-Silva: Well, they happen in a really like... what in my mind is kind of a classical painting process. They start as drawings, they move on to collaging, they get their colors worked out on paper, and then they finally kind of end up in their final form, which does involve a lot of pigment and paint. And I do think about them as paintings because I am like obsessed with paintings. And I kind of imagine them as paintings, even though they are very much about space. And they are very much about taking up space and involving kind of the space of the wall or the gallery.

AA: I was just listening to this podcast, and they were talking about the ways that religions really shaped visual language. And a lot of your work is very ingrained in a specific visual language. And they were talking about abstract versus figurative work and how, because of Christianity and the iconic nature of all the imagery, it really drives Western art. And then I look at your work and I'm like, it's so clear that you're completely... I mean not completely, but really rejecting hard figuration. It’s very organic, and almost... well, it is sculptural in the way that you produce the image. So I just wondered if that is something that you are cognizant of as you're making, that history of non-hard figuration within ancient culture.

CRS: Yeah. I mean, I would say that these grew out of a really specific drawing practice. I just had very little experience with painting in general, up until maybe like 10 years ago. Which for an artist, is kind of a relatively short amount of time. So I started drawing the landscape. And that was kind of what drew me to, like having a drawing practice even. So you know, there's something that's always really intriguing and not only about the landscape, but that the way kind the landscape is... I don't think interrupted is the right word. But the way the landscape has these elements that are inorganic, right? That have just been affected by humans.

AA: There is also an intense sense of control in all of your work as well.

CRS: Yeah, that's something that I struggled with actually.

AA: The inability to control or letting go?

CRS: Letting go of control which is why I kind of returned to some of these paintings that are in the back too. And so these have a little bit less control in them sometimes. You know, like, even though they end up being pretty tight, they are kind of trying to be a hard edge painting, a hard-edge abstract painting. But, you know, just the material itself doesn't let you have the cleanest line.

AA: And what is it... what exactly is the material that gives it a texture?

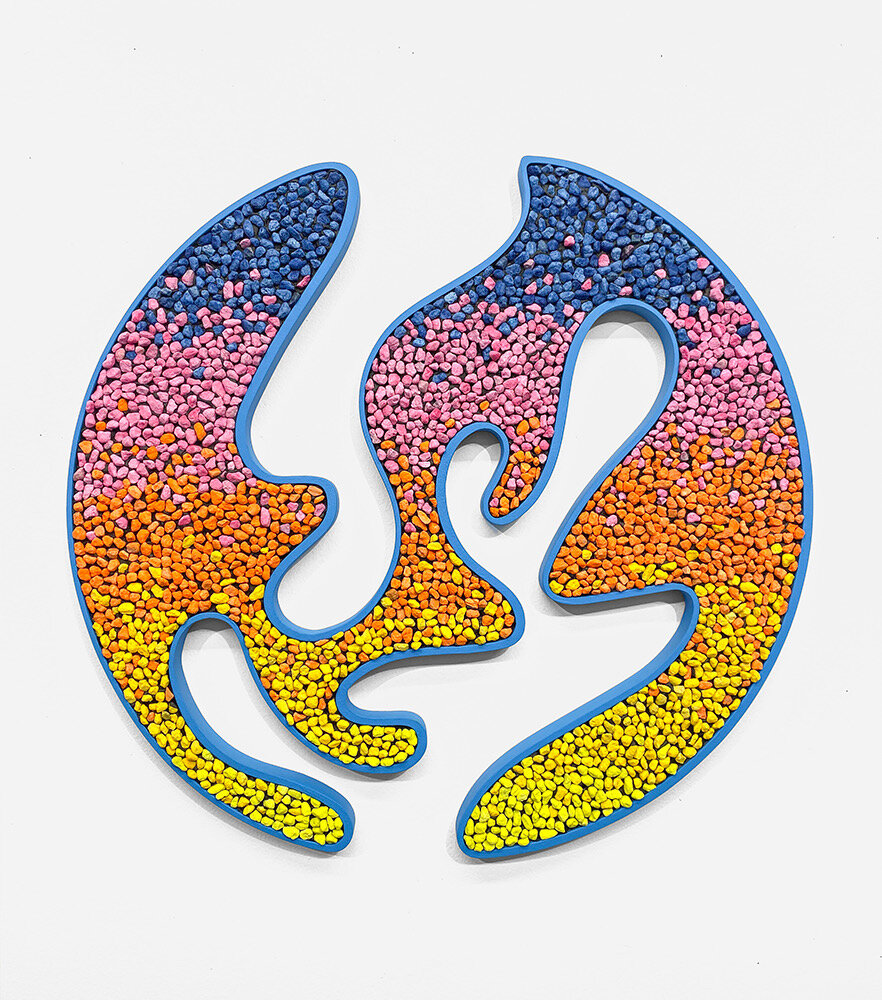

CRS: It’s some of the material that I'm making, it’s sand mixed with paints, sometimes it's like smaller stones that are mixed with paint.

AA: Okay, I thought it was ground stone.

CRS: Yeah, so it's sometimes sand and ground stone that gets mixed with the paint to give it that texture. And that's in different kinds of grades, I guess you would call it, like different kinds of thicknesses and sizes.

AA: And is the textural nature of them reflective of architecture, and the way that building facades can be?

CRS: Yeah, absolutely, I mean, I grew up in the desert, like often in the desert, you have to have like some sort of architectural material, like a facade to your building, so that the elements don't just beat down on the actual structure. The traditional way of building in the desert, where I'm from was to build a structure out of adobe bricks, which is a mixture of mud, and manure, and straw. And then you have that structure and you'd kind of plaster over it with this mixture. And so you end up having these really rich and beautiful textural walls, and people started, you know, carving designs into them just as decoration and so you end up with these really beautiful and unique surfaces that are everywhere, which then get painted on. And so there's kind of this idea I had, which was that I love seeing a painted surface, because the first paintings I ever saw are paintings that are basically murals. Paintings on the sides of buildings, paintings that sometimes have a giant popsicle because it's a popsicle shop, or like a restaurant. But they're also sometimes murals that are the history of the neighborhood, the history of the community, and a city that had a history that isn't documented, say, like, in a book, right? It's documented on the walls of the actual buildings that people live in.

AA: Even at small scale, even without the imagery being straightforward, it does give a lot of storytelling to me personally. And I think that's why I think maybe the textural paintings and the... we'll get to the ones in the back, are the most interesting to me, because there's this intense sense of storytelling, and I get it, even though I don't, and I know that there are cues that I'm missing, because it's not for me, necessarily.

CRS: But it's also like, sometimes they're just really simple ideas that are wrapped up into them. Like I was saying earlier, I'm looking at the landscape, most of the time. I'm looking at, almost like a landscape in terms of how you would look at something that is in front of you that is kind of vast...

AA: Broader themes.

CRS: Yeah, but like basic ideas about what a drawing is or what a painting is, like, what's in the foreground? What's in the background? And so for me, what is really interesting is to kind of confuse that space. So for a painting like this, where the color is kind of switching in and out, it's kind of hard to see what is in front of or what is supposed to be behind. And I love that kind of playfulness. And I love that disorienting nature about them.

AA: I like that you also refer to them as playful, because that's not a term that could be a good thing for an artist, referring to them as playful, but I do I agree. With beyond just the colors that you use, there is a sense of playfulness with I guess that push and pull and the gaps that are kind of existing there.

CRS: Yeah, I mean, it's something that I think I learned from a lot of different artists. You know, something can be both serious and also, like pushing the limits of what an artwork is. I mean, I just went and saw, you know, Jack Whitten's new show, in Chelsea...

AA: I haven't seen it yet.

CRS: ...It's incredible. I mean, there's so many different ideas of how paint can be applied and how a painting can exist. And I don't think I would necessarily call them playful, but they are kind of like playing with what is possible in artwork, you know?

AA: Absolutely. Talk to me a little bit about the scale of your work, because you are a mural painter, as well as working super tiny sometimes. And I just wonder what drives the scale? Or is it even something that you're considering in your process? Or does it happen somewhat organically?

CRS: It depends. Sometimes I feel like a real formalist, which means that I'm really interested in the scale of things, and the color relationships and the shapes and the sizes of things. And the textures. Obviously sometimes, I feel like I'm just kind of going through those considerations. But then there's all these other things that I'm thinking about that make its way into the work. But in that sense, I almost have like a formula that I use where I make probably 10 or 15 drawings every day. That's how I start my studio day. I'll draw, maybe one of them is good, maybe two of them are good, maybe they have some good ideas, but it's just a really nice practice to keep me loose and generating compositions and different ideas that can then expand right? Now that I've been working for so long, in this way, I can kind of like understand what's going to work at what scale.

AA: As a muralist ... do you consider yourself a muralist?

CRS: Sure.

AA: For me, when I think of murals, I think about the public nature of that. And that makes me think about community and how murals can be very integral in community.

CRS: Absolutely, yeah.

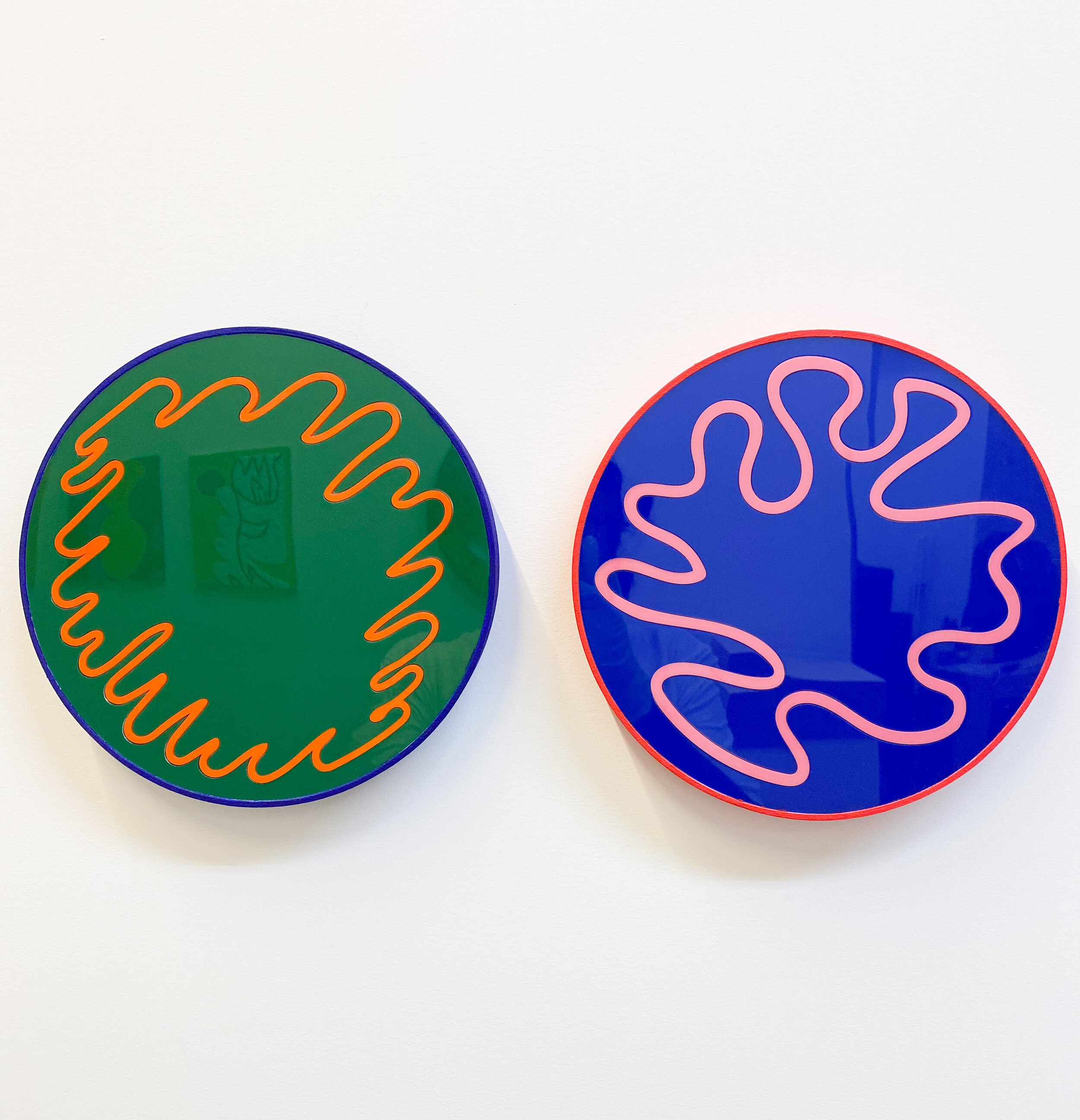

Install Image, Sunland Park. Image courtesy of artist.

AA: So, for you, because you've worked in a couple different spaces. I just wonder how you approach murals. This one in particular, is in a very specific type of architecture. And I just want to hear about how you conceived of this space within this space.

CRS: Well, this was a kitchen, I think, because there's like a water hookup. This whole space was an apartment at some point probably. But walking in here, [the gallery and I] had talked about, paintings up front and paintings in here. But it ended up being that those works in the front are so complete, I felt like they just needed to kind of exist on their own. And I had never really seen them exist on their own, but in my thesis project, they're surrounded by a mural...

AA: Oh right, that's true.

CRS: ...which was just like an itch I had to scratch, like, I wanted to see them in a complete environment. And that itch, in some ways got scratched even though it wasn't public, right? [laughs] You know, I saw them and they existed in that space for a while before I had to take it down. So I could understand how they function that way. But these paintings, in particular are studies. They're a composition that I came up with at the end of last year, which is like a color shift, and a texture study, and a shape study, and I decided that I could make them kind of infinitely. I have six more of these in the works right now.

Border Exchange Studies, 2021. Image courtesy of artist.

AA: The combination of colors is...

CRS: It just kind of like keeps going, you know? And they're also personally really useful, because I can see how different combinations of colors function, right? But in that sense, it's not that they're incomplete ideas, because they're actually maybe some of the most complete ideas that I have. Because they function, just like for this purpose. But they also kind of seemed like there was an opportunity to place them in a painted space. That made sense, because they themselves are about painted space. But yeah, when I came in this room, going back to kind of this idea about religion, it felt like a little chapel.

AA: I love that. But touching on the show at Cuchifritos for a moment, I remember, when I found out that you were going to have the zines as part of the installation, I was so excited because I had gotten one from you and I think that that part of your practice is really, really critical. Maybe to even just like who you are. This kind of sharing of information in... I mean, zines are sort of a traditional form of sharing information, but the way you approach it, and the way that it was worked into your final exhibition I just thought was really brilliant. And I wonder, moving forward, if at all, are you going to continue that melding of information sharing, and also what’s tied very much to your personal history? Like Salsita wasn't just, you know, something for fun, it was something that's really important to you.

CRS: Yeah, I mean, that felt like a really important moment, I had never... at Cuchifritos, I mean, I had never displayed a zine like that. That was in such close proximity to the kind of more object oriented works, because those things have always been kind of separate, my zine making practice, especially is rather new.

AA: Yeah, I really want to see that kind of mashup continue on, because your work is visually so beyond playful, like almost enduring and enthusiastic.

CRS: Well, you know, my practice encompasses a lot of research that doesn't always manifest in an object. Sometimes I think about these paintings as just a really involved and gratifying way of staying intellectually active, you know? It's like, the research exists because of the artwork. And the artwork exists because of the research. And so it just continuously keeps each other fed, basically. But then to be able to have it exist in these zine forms, or at least like short form personal essays has been, it's been lovely. Yeah.

AA: The other thing I've also come to notice, is that your work is really about where you come from. And New York City is so vastly different from El Paso. Just thinking about being along the border, is something I don't think that this audience necessarily considers a great deal. And it's not in your face. Like you're not beating us over the head with it, but you're definitely taking into consideration this part of who you are. So, to kind of expand what that identity is. It’s not just about being Southern, it's not just about being on the border of Mexico, there's a lot wrapped into that.

CRS: Yeah, I feel like when I think about my art practice, it's so much about learning more about my family. Learning more about the place that I grew up in, and continue to consider a home, you know? When most years I'm going back there at least three or four times a year, sometimes more like five or six.

AA: When was the last time you went back?

CRS: Not since... it will be like almost a solid year now. I went like right before, in January, I was there for Christmas. Not this past Christmas, I have been here obviously. But yeah, it's been a lot, longer than ever, I think.

AA: And you feel that longing for your home has affected your work at all? Or do you think that is just kind of always on the surface.?

CRS: It's just always there. I mean, there's moments where I miss the people, like my actual family. And I miss being home for sure. But it's something that like, I kind of sharpened into a thing I understand. I understand what I like about that closeness, like what interests me about it. And I can kind of like, feel about it from distance. When I'm home, it's a lot of going on hikes, drawing, going to visit people, like going to see things that I like, and then it's also just like being home, you know?

AA: It's interesting that when you're home, you have a lot more access, obviously, to like the landscape and nature element that we've discussed impacts your work. And being here has not at all diluted that.

CRS: It's only made it kind of stronger, it's like absence obviously, makes the heart grow fonder. And that's been very true. Because I think when you're there, you're just surrounded by it. And you're just immersed in it, it's only when you are taken out of it that you can actually see it.

AA: I have a very weird obsession with being in the desert, I've never been to the southwest. I just don't know why I'm so obsessed with going. I think that there's some harsh difference to what I'm accustomed to in New York City, and there's something that I feel like will slow me down. And I don't know, make me a little more at ease?

CRS: That's true. Just like, physically it'll slow you down, there's like not a lot of stuff out there. [laughs]

AA: I know! It's just, there's this majesty to the desert that I think I'm seeking out and I just hope that I actually enjoy it as much when I get there.

CRS: I think there's something about, it's just the sky is...

AA: Infinite and ridiculous.

CRS: ...It just seems to take up more space than how then it does anywhere else.

AA: And I think standing in front of this incredibly large blue circle [laughs] makes me think about how small I would feel in relation to it, and that's what it is.

CRS: That's true. It's an existential thing too. Really, it makes you feel like a part of the landscape, actually.

AA: Yeah, I think that might be what I'm desperately seeking out. Kind of recalibrating myself to understand how small I am in the grand scheme of things. It's a humbling experience, honestly.

CRS: Absolutely. Yeah.

AA: Especially being somewhere that is not familiar to you and also feeling incredibly out of place in it. I think it'd be a great experience. But now for the questions. Which artists’ work are you currently most drawn to? It could be contemporary artists or otherwise. First name that comes to your head.

CRS: Two things came to my head. One was that Jack Whitten show that I was mentioning. One because I'm obsessed with him, I don't know, for the last, five years? Like everyone else has been. And two is a friend, Edward Salas.

AA: Did you post him recently?

CRS: Yeah, so we have overlapping interests in terms of like material and color and history. [He’s] first generation from Colombia. So, we have all these similar experiences, but [the work] is very specific to his upbringing. His Colombian parents are very different to mine, but I love Edward’s work. I'm trying to figure out a way for us to work together.

AA: Interesting!

CRS: Well, that's kind of like a very successful thing for me, just like finding people that I'm inspired by, or people that I feel like we can have a really good kind of conversation with our works.

AA: And the works can also speak, got it. If not working as an artist, what profession would you pursue? Now, technically, you could answer this with something you have already done because you obviously do things outside of being an artist, but maybe something not art adjacent at all? Just another job, what do you think it would be?

CRS: I think I would love to be an archivist or something that involved research, that would be really interesting.

AA: That doesn't surprise me.

CRS: Something that would be even more different. I would love to be a furniture maker. Yeah.

AA: I could see that. I mean, that's not not art making, but I'll let it slide. [laughs] In your opinion, what was the best moment for black and/or brown artists and their work?

CRS: Oh, OK i see. What was the best moment? I feel like there's always been moments, but I got really excited thinking about now. I think now more than ever, we're kind of in control of our narratives. In a way, we have tools at our disposal to organize in different ways that we weren't able to before, just to connect and discuss.

AA: There is an opportunity to connect and maybe even spread much faster.

CRS: We also have the triumphs and the failures of the previous generations before us to learn from. And, you know, obviously, it's a little bit selfish because it's my era [laughs] but I do think that it's all of those things combined. It's a really lovely time. And also, really challenging, obviously, it will continue to be but it's really exciting.

AA: Right. Absolutely. What is the last work that made you capital FEEL something?

CRS: Capital FEEL something? I've been watching a lot of films lately, obviously because I'm home a lot.

AA: I'm familiar with your instagram film series yes! [laughs]

CRS: Well, I also watch actual film! [laughs] There is this Pedro Almodóvar movie called Volver that that I watched, rewatched. I hadn't seen it in... probably since it came out, which was like 10 or 12 years ago. It's just so beautiful. It's a kind of a story about two sisters and their mother, and their mother reappears as a ghost. And it's a really beautiful movie about these three women and their relationships to each other. And it has all the kind of - I don't know if you've ever watched Almodóvar’s movies, but he's really obsessive about a few certain topics that can be kind of problematic, one of which is just sexual assault...the relationships between men and women and violence and in some ways, they're kind of soap opera-y, except handling those topics in a very kind of serious way, but also kind of campy ways too. But he's a very complex filmmaker that follows his impulses. And also makes these really beautiful, almost Hitchcockian films.

AA: I don't think I'm familiar with it.

CRS: Really wonderful but I watched this movie a little bit, and it was like, I was crying by the end.

AA: Awww! [laughs] Ok. Last question, how, if at all, will your practice transform as we move towards a digital based market?

CRS: I don't know. I mean, I need to invest in a better camera. Like an actual camera. My practice is so object oriented. One thing that has kind of changed is that I love being able to just distribute zines as PDFs, and just be able to send them or to connect with people and be able to mail something out to someone physically, it's really easy. I mean, something that has really changed in my practice generally is that Instagram and social media allows me to just connect with people directly. It's really been the way that my art career has happened, basically.

AA: And I think even though a lot of your work is really tactile, I don't... I will never agree with a completely digital art experience. I guess because I'm such a... maybe a traditionalist? I think there's a completely different way of experiencing art in person.

CRS: Oh absolutely. There's nothing in the art world compared to it.

AA: Right, exactly. But because your work is so vibrant, it comes through beautifully.

CRS: Yeah, you can understand it, right? I think that is important.

AA: And I mean, and I'm just thinking about the ways that you've handled, both showcasing and selling your work via the internet. It's a conversation... I don't know where I fall in terms of it. Because I think that it's both an incredible tool to be able to utilize something like Instagram for getting your artwork to the biggest audience. But in the same breath, there's this weird push in the market now, like all these online spaces, and it's kind of dulling the experience for me a little bit.

CRS: Part of it is functional, but I feel like things were moving that way for a long time, like with Artsy, and those kinds of platforms.

AA: Yeah I love Artsy.

CRS: Yeah, it's great to see new artworks. Absolutely.

AA: And I mean, even if you're not in the business of buying, just for like researching what's out there.

CRS: I think that's one thing that's nice is that it kind of creates transparency about pricing.

AA: That's very true. It's very true.

CRS: You had to work up that kind of courage to go ask for the price list, which a lot of the times, if you weren't serious about buying something...

AA: I mean, I reached out to an artist earlier this week. I don't know that man but I asked him for a price list. [laughs] And we had like a very short conversation in DMs. And now I have the price list. And I'm like, that's definitely indicative of the time. I don't know that that would've happened even three years ago, there may have been like a way bigger vetting process. I'm not sure if he has a gallery or not, I can't remember. But there's definitely a loosening of this idea of like, who has access. And I think that is definitely a positive...

CRS: For sure.

AA: ...in the transformation of this digital world that we're entering.

CRS: Definitely.